`And There Appeared To Them Tongues of Fire’

The name glossolalia sounds as strange as the act itself. But this practice of praying in “unknown tongues” spreads, and brings prophecies of still stranger things to come.

The name glossolalia sounds as strange as the act itself. But this practice of praying in “unknown tongues” spreads, and brings prophecies of still stranger things to come.

(This was first published in The Saturday Evening Post of May 16, 1964.)

The Rev. Dr. Howard M. Ervin, a handsome, strong-featured man of 48, was attending a ministers’ convention in Miami when the strange experience began. Another minister put his hand on Doctor Ervin’s head, “and,” says the latter, “something like a series of bolts of lightning went down my spine.”

Doctor Ervin, who is pastor of the Emmanuel Baptist Church in Atlantic Highlands, N.J., did not understand what had happened, and he put it out of his mind for the rest of the day. “The next morning,” he recalls, “I woke up just soaked with perspiration. I did not know then that it was the heat of the Holy Spirit. As I stepped out of the shower and pulled a towel around my shoulders, I heard words rolling inside me. I thought, My subconscious is just regurgitating what I’ve been hearing here. But then I had a vision of ticker tape and I saw ‘Sa-da-ma-li’ printed. As I spoke this, a few more syllables came vocally.”

Shortly Doctor Ervin was using these words to pray: “Shan dama lai kushaiah hodhaiah salamah maciaiah Shan dama lai maciaiah muriah.” The words are not part of any known human language, and Doctor Ervin has no idea what they mean. “A while later,” he says, “I put my hands up and began to praise the Lord in these words He’d given me—and my tongue took wings. I just worshiped Jesus.”

Something similar happened to the Rev. Frank A. Downing, the 40-year-old pastor of Baltimore’s Belvedere Baptist Church. Praying in his study one evening, and feeling a strong sense of thanksgiving, “I began to praise the Lord, and in this spirit of praise I began to say words I did not know.” One night not long afterward he was awakened at about three A.M. and found himself unable to sleep. “I got down on my knees. Kneeling there by the bed, with my eyes closed in prayer, bright lights began to flash before my closed eyes, almost like lights running down an airstrip. There seemed to be some form to the lights, and I found myself praying, ‘Lord, if this is You, and You are trying to speak to me, slow these lights down so I can see.’ Almost immediately the lights slowed down, and they were letters, and they looked very much like the news flashes that sometimes run across the bottom of a television screen. ‘FEAR NOT.’ I read the words as they went by. ‘ONLY BELIEVE AND YOU SHALL Do SIGNS AND WONDERS IN MY NAME.’ The vision stopped as suddenly as it had begun. I took my Bible from the night table and wrote the words down in the flyleaf of my Bible. Then I got back into bed. It was only then that I realized that I had not put on the light and it was totally dark outside, but the room was illuminated by a light, and as I lay there with this light illuminating the area around the bed, it moved away from the bed and into the recesses of the room and began gradually to fade, almost like turning down a rheostat.”

What had happened to these two clergymen is happening to hundreds of others, and to thousands of laymen in nearly every major Protestant denomination in the United States. it is a rapidly growing movement called the Charismatic Renewal, from the word “charism,” meaning “a special divine or spiritual gift … conferred upon a believer as an evidence of … divine grace.” Those who take part in this movement claim to have experienced a wide variety of apparently supernatural phenomena, ranging from prophetic visions to miraculous cures of the sick. But the most bizarre such phenomenon is the sudden outpouring of prayer in unknown languages. This is known as “glossolalia,” or speaking in tongues. A young Presbyterian minister, for example, was struck by it while riding down a highway. “I’d drive along in my little car,” he recalls, “saying three words that God had given me. Then one evening as I was on my way down to the church for a wedding rehearsal. I was praying these three words, and I just broke forth into a whole language. It wasn’t anything that I had done. It was as though I had been striving to get through a prayer harrier, and the wall suddenly fell away.”

The charismatic movement began on a tiny scale in the major denominations in about 1956, with perhaps 20 ministers openly involved. The movement began spreading very rapidly in California in 1960 and has been gathering velocity ever since. It is now established in every state and has begun to appear in England and on the European Continent.

In the last three or four years nearly every mission board and every large Protestant organization has seen its ranks suddenly penetrated by this phenomenon. College students were quickly caught up in the movement’s advance. Students at Yale, Dartmouth, and Princeton Theological Seminary—including Phi Beta Kappa members—are now praying in unknown tongues. Charismatic prayer groups have sprung up in colleges and seminaries in at least 15 states in the Northeast, the North Central States and on the West Coast. Their appearance has astonished chaplains. “Charismatic time bombs are going off in schools and universities all over the country,” says the Rev. Dr. Harald Bredesen, a Dutch Reformed minister who is a sort of charismatic envoy to the nation’s campuses.

Praying in tongues has recurred at intervals throughout the Christian era, although it did not affect large masses until early in this century. Its advocates were quickly expelled from the established churches, whereupon they established the Pentecostal churches. For 50 years it remained the almost exclusive possession of the Pentecostal churches, which drew their members largely from the lower economic, social and educational strata. One of the most uncanny aspects of the current revival, however, is the way glossolalia has leaped out of its proletarian Pentecostal setting. Passing over the middle-class churches in between, it has made a startling appearance in the aristocrat of Christian communions—the august, decorous Episcopal Church w hose members largely conic from the best economic, social and educational quarters. Glossolalia thereby made an arc from pole to pole across the whole Protestant horizon. Subsequently the fallout from this arc has been showering down upon Methodists, Baptists. Lutherans. Presbyterians and Congregationalists. as well as many smaller denominations.

Today it represents a broad cross section of American Protestantism. According to Dr. Stanley C. Plog, a psychologist at the University of California who questioned more than 350 members of the movement, it includes more than 40 separate denominations, though the largest groups are Episcopalians, Baptists and Presbyterians (11 percent each). He found incomes ranged from $100 to more than $1,600 a month, educational levels varied from three years’ schooling to graduate degrees. Curiously enough, he found that a large majority were Republicans. As a whole, he found the movement to be “a reaction to mass society, a reaffirmation of the individual and his importance.”

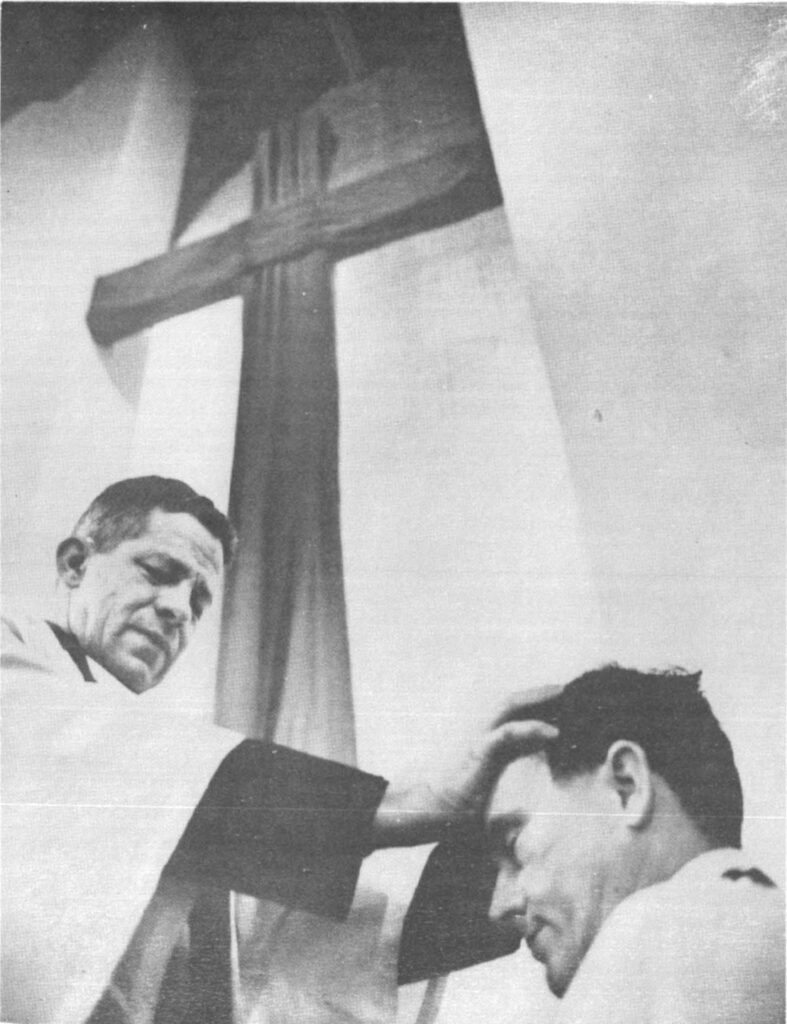

In service at Trinity Episcopal Church in Wheaton, ill., Rector Richard Winkler lays on hands to transit the experience that inspires glossolalia.

The spread of this movement has dismayed a number of Protestant leaders. Some fundamentalists call it a “work of the devil,” and Dr. William Culbertson, the president of the Moody Bible Institute of Chicago, one of the country’s oldest fundamentalist schools, warned the entire student body against praying in tongues. In California Bishop James A. Pike has put a virtual ban on praying in tongues within his diocese. A pastoral letter went out a year ago from his office in Grace Cathedral atop Nob Hill in San Francisco and was read in all the Episcopal churches of central coastal California. Noting that “a number of our clergy and hundreds of our laity have personally experienced this phenomenon,” Bishop Pike declared that the use of glossolalia had reached a point at which it was “dangerous to the peace and unity of the church” and a “threat to sound doctrine and policy.”

Warning of “heresy in embryo,” he urged the clergy “not to take part in the movement to nurture and spread the practice of speaking with tongues and not to invite preachers or speakers who have this purpose.” Ministers both for and against glossolalia see the practice as a possible threat to the present order of things. Some welcome this because they think the established order has become anemic or irrelevant and badly needs shaking up. Others are appalled. Several denominations, including the Episcopalians, have launched formal investigations.

To adherents of the charismatic movement, their beliefs are fully supported by the Bible—specifically in the second chapter of the Book of Acts: “And in the last days it shall be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy…. And I will show wonders in the heaven above and signs on the earth beneath, blood and fire, and vapor of smoke….

In the same chapter occurs an account of the event to which believers in the gift of tongues hark back for inspiration. On the day of Pentecost the disciples were gathered to pray in Jerusalem when “suddenly a sound came from heaven like the rush of a mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared to them tongues as of fire, distributed and resting on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.” (Acts 2:2-4)

To the believers in the charismatic movement, these words must be taken literally. “More or less commonly in Protestantism we’ve believed many of these historic reports of miracles and supernatural events, but we’ve regarded them as something for another time,” observed Dr. Francis E. Whiting, director of the department of evangelism and spiritual life of the Michigan Baptist Convention. “We’re just as rationalistic as we possibly could be. This is the disease of the church. The only way I know that a genuine renewal is going to come is for us to find the religion of the New Testament—which seems to me a very powerful religion, not too widely seen. Ever since I was called to the ministry, I have had the inescapable conviction that the New Testament means exactly what it says—the miracles and supernatural events and particularly this matter of knowing Jesus Christ as a personal, inner reality. I’m not at all interested in talking in tongues as such, but I am interested in finding the life of the New Testament. We’ve got to find this, because if we don’t, we’re going to go out of business. By the year 2000 the pagan population of the world is going to grow from two billion today to about five billion. All we have to do to go out of business as the Christian Church is to stay in business as usual.”

The Very Rev. John J. Weaver, the tall, white-haired dean of Detroit’s Episcopal Cathedral of St. Paul, puts it even more forcefully. “The disease today is nihilism—nothingness,” he says. “And I don’t mean philosophical nihilism: I mean lived nihilism, the kind you find in hospital beds, in the office. The problem today is lack of power, spirit. The bones are dry and dead. We need a new strengthening of the spirit. I think the reason we are seeing speaking in tongues today is that the world is so fragmented and torn, and in the midst of all this loneliness and fragmentation the Christian needs a fresh indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

“I don’t think the Christians were singing Quo Vadis in the Colosseum: I think they were praising the Lord in tongues. There is no essential difference between ‘the man in the lonely crowd’ today and the lonely man who was thrown to the lions except that different kinds of lions are eating him up. Today’s man is fighting invisible animals. The Lord edified the other man by giving him the gift of tongues.

“Ministers from virtually every denomination have received the gift of the Holy Spirit in our cathedral,” he added. “I don’t know where they come from, how they get here, but they come.”

The most widely known, and one of the original, charismatic meetings is held in the United Presbyterian Church at Upper Octoraro, Pa., on the rural fringe of Philadelphia. The white-stuccoed stone building, in continuous use for 120 years, sits on a grassy rise amid the hills and hollows of 20 pleasant acres. Giant white oaks, taller than the church, raise ancient arms in silent benediction. On Saturday nights cars from at least three states swing by cow sheds and cornfields into the church parking lot.

Here, six years ago, the meetings began with five to eight people in attendance. It was a routine prayer session until one after another of its members broke forth into tongues. Marianne Brown, wife of the Rev. James H. Brown, was first. She was filled one night with a feeling of thanksgiving for the healing of her daughter, and she began to pray in tongues. Pastor Brown says he cannot explain how the eight-member prayer meeting grew to its present average size of 200 to 300. “I never advertised it,” he says, “but word got out, and the Spirit of God just began to draw people. One night we had 600 here. We’ve had five Episcopal rectors in the meeting at one time. We get a good representation of Methodists, Presbyterians, Baptists, Mennonites, Quakers, Episcopalians. Nothing can keep them away—snow, ice, slush, rain. They come.”

Pastor of the church for 24 years, the Reverend Mr. Brown is a lean, tall, cordial man who laughs a good deal out of what appears to be sheer delight. In the prayer meetings he sometimes becomes so lost in adoration that he raises his head and arms to heaven and lifts his feet lightly in place in an act of worship called dancing before the Lord. On Sunday mornings he conducts a formal worship service in the regular Presbyterian order, without charismatic manifestations.

“Our major function is praise, Mr. Brown explained to me before one of the Saturday-night meetings. “We use the Old Testament Psalms as our worship manual, and we do exactly what the Psalms tell us to do. We lift up our hands in the presence of the Lord and we magnify Him with our whole heart. We sing a hymn over and over, and each time the spirit of praise gets higher. At the end of singing it in English, we may sing it in the language of angels.”

When the meeting began at 7:35 that evening, there were seven other ministers present. Pastor Brown stood at a plain wooden lectern and looked out over his congregation, mostly young adults. The meeting moved at a quicker pace than formal worship services, and there was a large measure of direct participation by laymen. Though there were several short addresses by ministers, there was no sermon. There were prayers, Scripture readings, solos, many hymns. Faces beamed as the churchgoers sang We’ll Give the Glory to Jesus. Later several wept as Abide With Me was sung softly twice in succession. Then a red-haired youth of about 20 stood and said he had struck his head on something in the afternoon and still felt dizzy. Six people rose in various parts of the congregation and surrounded him. They placed their hands on his head, lifted their faces toward the ceiling and prayed silently, their lips moving, for a minute or two. Then they returned to their seats. There were rapturous smiles on many upraised faces as His Name Is Wonderful was sung at length. The music stopped.

“Let’s just praise Him,” Mr. Brown said. Some of the people began singing in low chanting tones that rose and fell in a sort of liturgical pattern. Behind, melody could be heard with such impromptu exclamations as “We love Thee, O Lord,” “His mercy endures” and “Glory to the Lamb.” Nearly all hands were raised overhead. Tears streamed from a young woman’s eyes. The singing ended very suddenly, as if by signal, though there was no signal, and the hall became profoundly silent.

Into the silence a woman began to speak in tongues. Her voice was tiny and, but for the depth of the silence, would have been lost. When she finished, the Reverend Mr. Brown waited perhaps eight seconds. Then, with eyes closed, he gave this interpretation:

“I shall have a people, saith the Lord, who shall do exploits in the land and be a praise unto my name. The sick shall be made whole, those bound in prison houses of sin shall be set free, for I will yet demonstrate in the land that I am the Lord of hosts and the King of kings. So shall signs and wonders be wrought in the earth. I shall be thy courage when thou art afraid, and thou shalt bring glory to my name.”

Several visiting ministers spoke. One of them, a Presbyterian, told the meeting, “I came all the way through the ranks of conservative teaching, and my heart breaks, because conservative Christians sometimes call this fanaticism. But I say that unless you and I get fanatical, we will have a dead Christianity!”

Pastor Brown dismissed the meeting at 10:15 but invited those who needed special help to come forward for prayer. Eleven people knelt at the edge of the pulpit platform. Two or three ministers or laymen went to each, standing or kneeling beside the worshipers to pray and give counsel. The lights in the church did not go out until 12:30 A.M.

As in this meeting, the charismatic movement often includes not just speaking in tongues but a whole variety of apparently supernatural events. On the West Coast it is alleged that “tongues of flame” have fleetingly appeared during some charismatic services. The wife of a Methodist minister tells of a “room that was filled with a beautiful, supernatural blue light.”

On a wet, snowy night in February, 1962, a young sales engineer named Ronald Haines was flying home from New York to Richmond, Va., and recalls that “everything was fine until we got over Washington. Then the captain came on the P.A. system and said he thought we had damaged the front landing gear in taking off. He told us to prepare for an emergency landing.” At home in Richmond, Ronald’s wife, Mary, an Episcopalian, was reading in the living room, but something troubled her. “I had a nagging feeling I should pray,” she says. “It was extremely persistent.”

In the plane, men were stationed at the emergency exits and told how to get them open. “We were told to lean forward as we landed,” Ronald says. “There were fire engines below and the field was closed.” The time was 9:30 P.M.

“I went into the dining room and started praying at twenty past nine,” Mary says. “As soon as I got on my knees I had a vision. I saw a plane coming down, and when it landed, the wheels went out from under it. Suddenly it tipped over on its side and a fire blazed all, around it. For twenty minutes I prayed both in English and in tongues. Then this nagging feeling I’d had all evening was suddenly gone.” Three hours later Ronald walked in the front door. “Boy, did we have a close call!” he exclaimed.

“Wait,” Mary said. “Let me tell you what happened.”

Does praying in meaningless sounds really serve any Christian purpose? I asked the Rev. Morris G. C. Vaagenes Jr., 33-year-old pastor of a Lutheran church just outside St. Paul, Minn., precisely what glossolalia does. “It’s getting something off your chest,” he said, “in a way that just praying with your conscious mind can’t. When we pray with our conscious mind, only a fraction of our total mind is able to pray. Praying in tongues gives the subconscious a chance to express itself, so that one’s whole being, one’s whole personality can speak to God. When a person doesn’t know what to pray for, he can pray in tongues and grapple with the matter through that prayer, and many times the answer comes to him immediately afterward.”

The young minister said he discovered that the Lutherans who were praying in tongues were not people of low intelligence but instead just the opposite—they were highly respected in the church, and included some of the ablest pastors and some of those of highest rank in their seminary classes.

Pastor Vaagenes began a weekly meeting in his home, and in less than a year seven other groups, four in Minneapolis and three in St. Paul, sprang directly out of it. “When you find that you have people sitting up the stairway,” remarks an Episcopal rector, “it’s time to form another group.” Once a month all these groups meet together in a church.

“In our house meetings we put a chair in the center of a living room filled with twenty-five or thirty people,” he said. “We state that if anyone desires prayer or the laying on of hands for some specific need—a hunger for the anointing of the Holy Spirit or if they need healing—to take the chair and share the desire with the group. Different people gather around to join in prayer and lay on their hands. There may be tongues spoken at this time, or there may be prophecies that come for the person. We sense a real presence of God at such a time.”

In his pastoral letter warning against the practice of glossolalia in the California diocese, Bishop Pike disparaged the feeling of discovery that excites practitioners of tongues. “Glossolalia,” he said, “is a psychological phenomenon which has been known over many, many centuries, quite apart from any particular religious orientation; in more extreme forms it is associated with schizophrenia.”

Behind the pastoral letter was a 20-page report by a nine-member study commission that reported to the bishop. Its members included two practicing psychiatrists and six clergymen. The report said glossolalia had been widespread in the mystery religions—“It is referred to by Plato, Vergil, Plutarch and early Egyptian writers”—and that it was not, per se, a religious phenomenon.

One church that has come under the restrictions of the bishop’s letter is Holy Innocents Episcopal Church in Corte Madera near San Francisco. It is a high-church parish, and inside the small building mobiles slowly twist and glide. Its rector, Rev. Tod W. Ewald, is a cordial, outspoken and rather authoritarian priest. Before he received the “infilling of the Holy Spirit,” Father Ewald had been regarded by other ministers in Corte Madera as dogmatically contemptuous of expressions of the faith that did not coincide with his own. “Now the walls have just crumbled down,” he said. “We’re all one in Christ. I could no more have said that two years ago than fly.

“We have 350 members, and one third of them have spoken in tongues at our altar, with beauty and wonder and reverence,” he said. “We received this Pentecostal experience at the altar rail by laying on of hands.” Parishioners from 20 to 70 who had received the experience told of estranged husbands and wives finding renewal of love, of atheist relatives suddenly reaching for God, of off-and-on churchgoers becoming twice-a-week attenders, of tranquility and a new effervescence. “You just bubble, bubble, bubble,” one man said.

Ministers in and out of the charismatic movement recognize hazards of potential abuses, however. The charismatic experiences can create a strong bond across denominational lines, but within single congregations they are sometimes extremely divisive, especially when there are members who are scandalized by speaking in tongues. The most frequently heard complaint is that glossolalia engenders spiritual pride among those who exercise it. The Pike commission admonished those in the movement against teaching that “glossolalia is the essential sign of God’s presence and that those lacking it are in any sense second-rate citizens in His Kingdom.” To this, most Protestant leaders say a fervent “Amen.”

Charismatic ministers say that the excesses of glossolalia, both in this century and in the early church, have been its public use out of turn. According to his writings, the Apostle Paul prayed much in tongues, but he took a dim view of glossolalia in church. Though he wrote that “I thank God that I speak in tongues more than you all,” he laid down very specific limitations on its public use, ordaining that no more than one person speak in a tongue at a time, and that there be no utterance in tongues unless someone is present to interpret. A person who “speaks in a tongue edifies himself,” the Apostle states, whereas the purpose of a public worship service is to edify the entire congregation.

Though ministers report that church members who exercise charismatic gifts usually serve the church far more actively than the average member, they admit that a few develop a “free-lance” attitude, find it hard to submit humbly to the judgments of others and tend to regard themselves as qualified arbiters of a whole range of matters. Sometimes they even switch from church to church, going wherever they will find an audience. Worst of all is the danger of outright counterfeit. The charismatic movement has been troubled at times by people who pretend to gifts. There is a thin line between faith and credulity, and if it is not scrupulously observed, virtually any sham can be put over in the guise of a spiritual gift. “The cure for abuse is not disuse, but proper use,” a Lutheran minister says to this. “A disciplined ministry will hold potential abuses in check.”

Charismatic ministers say that since the central claim of Christianity is that Jesus Christ is alive and is all-powerful, the church must proclaim Him so today if Christianity is to seize the initiative from powerful pagan world movements. They argue that to deny the supernatural character of Christianity is to deprive the church of its essence and to reduce its teaching to an optional, take-it-or-leave-it moral code. “There ought to be something to distinguish the church of Jesus Christ from a Rotary Club,” one minister said. The celebrated religion boom of the 1950s crowded the churches but failed to produce any notable rise in morality or social welfare. And there was widespread talk that the world had entered a: “post-Christian” era. Many ministers believe that supernatural gifts were invested in the early church for the emergency of the Apostolic generation, when the church had to survive harrowing hostility—but charismatic ministers argue that the world is as precarious for Christianity right now as it has ever been. “There is a kind of mystic violence abroad in the world today,” says the Rev. Dr. John MacKay, president emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary and one of the foremost ecumenical figures of the time. “In my mind this is surging up in the secular realm at the end of an era, and you have got to match that in the religious realm so that religion becomes a very, very exciting thing that absorbs your whole life in the principle of commitment.

“In the secular realm we see people like the beatniks and the delinquents who have just got to get their whole emotional being in some direction, even in the wrong direction. But the church is orderly. That hour is over,” he said, adding a warning: “You could get the historical churches irrelevant to the human situation. One reason is that they’re unwilling to face the realities of the kind of relationship to deity which becomes a very exciting thing. They’re scared to death of anything that will get your life.

“We are at the end of an era,” as Doctor MacKay sees it. “Revolutionary, volcanic forces are at work, and our people won’t face that. We just don’t want to look at it, you see, at the very time the volcano is erupting.”

“Revolutionary, volcanic forces are at work, and our people won’t face that.”

As the controversy over the resurgence of glossolalia continues, the charismatic himself feels no need to formulate reasoned explanations. He repeats a favorite maxim: “The man who has an experience is never at the mercy of a man who has an argument.”

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the charismatic movement is its belief in faith healing, a belief which medical scientists completely reject. “Our healing ministry is carried on in my study in church after services,” says the Baptist Rev. Howard Ervin. “We have seen at least six men instantly relieved of addictions of long standing. We saw a blood clot disappear immediately. An appliance repairman who had torn cartilages in both knees was healed instantly. He could barely walk when he came in for prayer, and afterward he ran out of my study and down five steps to his car. He was absolutely free.”

The Baptist Rev. Frank Downing of Baltimore reports a similar experience. A woman approached him after a service and said her son had suffered so many abscesses of the ear that scar tissue was mounting from repeated lancings, and her doctor feared the boy’s hearing might be impaired. The Reverend Mr. Downing visited the home and found a little preschool-age fellow lying on the couch in great pain.” He prayed. When he finished praying, he saw that “there was a discharge coming from the ear.” The pain left and the boy seemed well. The next morning the doctor could find no trace of the scar tissue.

While scientists dispute such “cures,” they are equally puzzled by the phenomenon of speaking in tongues. Commonly, when a charismatic speaks in tongues, another member of the group will interpret the message. Less involved observers, however, have grave difficulty making sense out of glossolalia. A survey made by the Episcopal Church found that glossolalia “stresses open vowels and a general lack of harsh gutterals, somewhat in the manner of Hawaiian or a Southern romance language.” Research for the report was based on repeated hearing of this form of prayer. Quite often it sounded to the ear of the investigator like some form of Chinese or Far Eastern dialect:

Baptist minister: “Sala ka taiyestsa. Sai chung tung chava dieva zandali cheya chungolo mochoko kotorie toka. Chang chung kuye sayesheh neveesaya….”

Episcopal priest: “Okhazhevanai toree kafaouzheevra doudela. Zhour dena dasteeprathos dai brou zheedavra taneen.”

Despite its widespread and continuing occurrence among Christians in this century, glossolalia seems never to have received an expert linguistic analysis—except once. Tape recordings of Doctor Bredesen—the campus missionary—praying in tongues were played to a group of linguists in Toronto. The conclusions of the assembled scholars were set forth in a 2,260-word analysis which went into deep detail about “alveolar and alveopalatal, labial and velar” sounds, and declared these sounds “closest to some of the Malayo-Polynesian languages.” But it was found to be “highly improbable that this is a human language.” It was also stated by the director of the study that for Doctor Bredesen this was undeniably a “spiritual experience.”

“If this had been gibberish,” says Doctor Bredesen, “wouldn’t they just have said so?”

Next July Doubleday will publish the first full-length study of the glossolalia revival, Tongues Speaking:. An Experiment in Spiritual Experience, by the Rev. Morton T. Kelsey, rector of St Luke’s Episcopal Church in Monrovia, Calif. Though Father Kelsey is not himself a glossologist, he has observed the phenomenon in 30 members of his church, including his assistant rector. “My basic feeling,” says Father Kelsey, “is that glossolalia comes out of the collective unconscious.” This is a conclusion drawn from studies at the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich and a correspondence Father Kelsey had with the late Doctor Jung himself. It was Jung who originated the hypothesis that each human psyche is in contact with a vast reservoir of collective experience out of which human consciousness has arisen.

As Father Kelsey explains it, speaking in tongues is similar to dreaming. “In a dream,” he says, “the ego is relaxed, and another part of the psychic structure takes over so that images present themselves to the consciousness. In tongues, instead of a visual image coming before the consciousness, you have a motor response taking over.” Father Kelsey says that glossolalia is the product of “no neurosis, no psychosis, no seizure and no hypnosis. A person can turn speaking in tongues on and off like a faucet. There is no more seizure than in going to sleep.”

Those who speak in tongues do not always use meaningless words, however. “A missionary who had served in Mexico came to us,” says Doctor Ervin, “and asked us to anoint her and pray for her healing. I prayed in tongues, and when I finished, the missionary said that I had prayed, ‘God be propitious to this needy soul’ in Spanish. I do not know Spanish.”

For a time Doctor Ervin’s wife Marta was antagonistic to the charismatic movement, but she said that at one meeting she heard “an Italian fellow who spoke atrocious, broken English that was just irreparable. And then, when he spoke in prophecy, he spoke the purest English, in an elevated diction and style. It was simply beautiful.” That. convinced her, she said, of the possible validity of prophetic utterance today.

Charismatics at meeting in New York City feel the spirit and show the outer signs.

(This was first published in The Saturday Evening Post of May 16, 1964.)